Existentialism, Negritude, and the Search for New Meaning

Read More

The early twentieth century was a time of tragedy in Europe. The physical destruction of warfare was rivaled only by the accompanying loss of faith. One of the most powerful values at the time was that of nationalism—pride in one’s country. The value of nationalism was destroyed, not only by the realization that its consequence was war, but also by humbling experiences of invasion and occupation, and the growing influence of Marxism. Only the United States, which participated but was never occupied, seems to have retained the naïvety and enthusiasm of nineteenth century Europe. The heralded values of science and technology, rather than being a blessing, produced instruments of death and destruction on an unprecedented scale. The discovery of the extermination camps and the use of the atomic bomb at the end of WWII demonstrated clearly the horrors that were the product of western culture. Those values which had been previously held up as a model for the rest of the world, were revealed to be the harbingers of disaster.

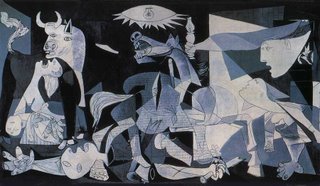

Where European art had been dominated by “realistic” images, it was now felt that this type of art could not properly convey the experiences of chaos and disorder experienced during the war. The values associated with realistic art are also associated with science and the western myths that made the war possible. Thus art produced during and after WWII would no longer strive for “accuracy”, but for images that captured a subjective (and thus honest) experience, such as Picasso’s depiction of the bombing of Guernica, Spain. Artists and philosophers were charged with the task of creating new images and values independent of God or Reason.

Where European art had been dominated by “realistic” images, it was now felt that this type of art could not properly convey the experiences of chaos and disorder experienced during the war. The values associated with realistic art are also associated with science and the western myths that made the war possible. Thus art produced during and after WWII would no longer strive for “accuracy”, but for images that captured a subjective (and thus honest) experience, such as Picasso’s depiction of the bombing of Guernica, Spain. Artists and philosophers were charged with the task of creating new images and values independent of God or Reason.Existentialism gained great popularity in France after WWII, when Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, who had been members of the resistance, were held up as the new prophets of French thought. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus argues that “even within the limits of nihilism it is possible to find the means to proceed beyond nihilism” (from the preface). Camus began by accepting as a foregone conclusion the absurdity of the world. Given that, he attempts to answer the “one truly serious philosophical problem... judging whether life is or is not worth living” (MS3). He wants to prove that it is, but without succumbing to the “nostalgia for unity, that appetite for the absolute” which is the “essential impulse of human drama” (MS17). He limits himself to certain immediately perceptible knowledge, which he describes as “lucidity”. “The world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction.” (MS19). Science cannot answer this problem. It can “describe”, “enumerate” and “classify”, but ultimately it “ends with a hypothesis” (MS19-20) “Blind reason... may claim that all is clear; I was waiting for proof and longing for it to be right. But despite so many pretentious centuries and over the heads of so many eloquent and persuasive men, I know that is false. On this plane, at least, there is no happiness if I cannot know.” (MS21). However, instead of despairing, Camus affirms his life. “The absurd man thus catches sigh of a burning and frigid transparent and limited universe in which nothing is possible but everything is given, and beyond which all is collapse and nothingness. He can then decide to accept such a universe and draw from it his strength, his refusal to hope, and the unyielding evidence of a life without consolation.” (MS60). Thus Camus “makes of fate a human matter” (MS122) and by a sheer force of will, he concludes that “all is well” (MS123). Camus’ writings are some of the most important of the post-war period. His work is both an example of the new direction of literature in the twentieth century, and also an expression of the grim tone that was felt all over Europe during those years.

In the nineteenth century, France was one of the greatest and most prestigious empires. The French identity was based around the preeminence of French civilization and culture. Thus, for the people of France, the clearing away of old values was a great blow. In the Caribbean, the experience was quite different. The realization that European values were false was not a condemnation, nor a cause for despair, but rather an opportunity. Where France had benefited greatly from the systems in place before the wars, the people of the Caribbean had been oppressed as has hardly been seen in the history of the world. Nazism may have ravaged Europe, but slavery and colonialism had ravaged Africa and the Caribbean for centuries. Césaire, speaking of the European middle class tolerance of colonialism said:

Nazism they tolerated before they succumbed to it, they exonerated it, they closed their eyes to it, they legitimized it because until then it had been employed only against non-European peoples; that Nazism they encouraged, they were responsible for it, and it drips, it seeps, it wells from every crack in western Christian civilization until it engulfs that civilization in a bloody sea. (BSWM90)

The horrors that Germany inflicted on Europe were prefigured by those that Europe inflicted on Africans and their descendants. At the end of World War II, when Europe finally won freedom from the Nazis, the people of the Caribbean found themselves still under the yoke of colonial control. (Senghor: “Lord, forgive France, who hates occupying forces and yet imposes such strict occupation on me”, LSSCP71) Colonialism was no longer a tolerable condition. The myth of the superiority of European culture had been dispelled, and the time of decolonization had arrived.

In Black Skin White Mask, Fanon argues that “by calling on humanity, on the belief in dignity, on love, on charity, it would be easy to prove, or to win the admission, that the black is the equal of the white. But my purpose is quite different: What I want to do is help the black man to free himself of the arsenal of complexes that has been developed by the colonial environment.” (BSWM30). It is not possible to convince whites to “stop being racist”, but even if it were, it would not relieve blacks from their own self-hatred. According to Sartre, the gaze (le regard) is a way that more powerful groups objectify less powerful groups. The powerful may sit in judgment without being judged. The powerful define the structures of the world, and success requires one to work within those structures. It is very difficult to work in a structure without accepting the values that it implies. The stories of the powerful thus become accepted truth. The less powerful cannot choose their own destinies. They are forced to see themselves through the eyes of the other. In order to restore equality to the colonized, the oppressed must first create new lenses with which to view themselves, they must tell new stories that celebrate their unique existence. This was the first goal of Negritude: to return the gaze. In Orphée Noir, Sartre writes: “Here, in this anthology, are black men standing, black men who examine us; and I want you to feel, as I, the sensation of being seen.” (ON7). In creating a powerful black perspective, Negritude forces whites not only to change their conception of blacks, but of themselves. “A black poet, with never a thought of us, whispers to his beloved... and our whiteness appears to us a strange white varnish which stops our skin from breathing” (ON8). The poet of whom he was speaking is Léopold Sédar Senghor. In his poem Portrait, Senghor speaks with a voice conscious of what Europe has to offer:

Now the European spring approaches me

Offering me the land's virgin scents,

The smiling facades in the sun,

And the grey mildness of roofs

In sweet Touraine.

Perhaps he enjoys the offering, but he also sees through the façade. The mildness of Europe is belied by the frigid curse of colonialism. Soon, Africans will emerge from their hibernations, and the strength of their demands will be greater than those of foreign empires. For now, he waits, appreciating the beauty of the land of Woman.

It still doesn't know

Winter has sharpened my stubborn rancor

Nor the demands of my imperious negritude...

Today, I am content with just the smile

Your precious lips sketch out,

Lost in the sea dream of your eyes

And the wild hill of your hair

Rustling in the wind!

Negritude found a guiding aesthetic and philosophical support in the critical theories of Surrealism. Unlike existentialism, which denied the validity of faith, Surrealism held some truths to be sacred. It rejected European bourgeois values, but rather than foundering in nihilism, Surrealists responded swiftly with a “sacred yes” to “Liberty, life, [and] poetry” (RS174). Surrealism in Europe, which was most popular before WWII, was somewhat narcissistic. It was concerned with liberation, but on an individual scale. As it was primarily practiced by the white middle class, it thus lacked a certain amount of legitimacy in its claims of oppression. But when Surrealism arrived in the Caribbean and Africa, “it extended and renewed itself in negritude, which could have been its coloured child.” (RS228). Negritude was a great realization of Surrealist ideals, both because of the power of its voices (Césaire, Senghor) and also because of it’s scope—Negritude promised liberation not for a single person, but for a whole people, and ultimately, for all people.

In Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, he not only proclaims the death of God, but as a poet, a creator of new values, he proclaims himself His murderer:

I have assassinated God with my laziness with

my words with my gestures

with my obscene songs

and then, celebrating the birth of new values and clarifying his purpose:

oh friendly light

oh fresh source of light

those who have invented neither powder nor compass

those who could harness neither steam nor electricity

those who explored neither the seas nor the sky but whose

without whom the earth would not be the earth

gibbosity all the more beneficent as the bare earth even more earth

silo where that which is earthiest about earth ferments and ripens

my negritude is not a stone, its deafness hurled against the clamor of the day

my negritude is not a leukoma of dead liquid over the earth’s dead eye

my negritude is neither tower nor cathedral

it takes root in the red flesh of the soil

it takes root in the ardent flesh of the sky

it breaks through the opaque prostration with its upright patience

The light Césaire sees is the reflection of his newly-created images of himself and his people. Even if black people were not responsible for the things most celebrated by western civilization, but they are nonetheless essential to the earth. He does not wish to launch himself, viciously and futilely, against the west. Nor will he be blinded, his eyes filled with the rot of a dying white civilization. He takes root in his history, which is dark and bloodied, but which contains passion, and infinite promise. Finally, he breaks through the “opaque prostration”, which is the bondage that all experience when they are defined by color, and passes on to a future transparency where all may stand upright. Even as he proclaims the strength and roots of his people, he simultaneously transcends the limits of that specificity, and thus Negritude becomes universal.

Conclusion

According to René Ménil, the great Martiniquan Surrealist theorist, “The unity of dream and action within man shows that not only is it possible to reconcile our life with our dream, but that it is necessary” (RS154). If, by the rituals of poetry and art we are able to transform our dreams, then we will also transform our actions. Thus, the “marvellous” (the stories that define our world view) “is the image of our absolute liberty. But a symbolic image.” (RS92). We may change ourselves, and by example, others may be changed as well, but we cannot alter the physical laws of the universe. We cannot move mountains save by our own hands. The magic of poetry is not the ability to effect one’s will upon the world without action, but to choose one’s destiny and through one’s actions fulfill it. This is the practical limitation of creation, and the only one of concern for Surrealism. But for the existentialist, another danger exists: dwelling on the tragedy of a lost faith. The final limitation of constructed value is that it is the only value. The sometimes dark tones of existentialism are fundamentally determined by a psychological state—the experience of grief. As when Orestes speaks with Electra in Sartre’s The Flies, “I am free, Electra. Freedom has crashed down on me like a thunderbolt.” “Free? But I—I don’t feel free. And you—can you undo what has been done? Something has happened and we are no longer free to blot it out. Can you prevent our being the murderers of our mother—for all time?” (NE105). He cannot; and neither can we return to a belief in the absolute. Our knowledge, whether we chose it or not, has expelled us from that garden. But this is only a problem if we perceive it to be. As there are no absolute demands of us, we may choose to love life, and thus be satisfied. “What! By such narrow ways—?” (MS122). When Camus says “One must imagine Sisyphus happy”, he does not mean merely that one must have the idea of Sisyphus smiling absurdly, but that one must create this image of man for himself as one creates all value. If we acknowledge that purpose derives only from our own will and what is wrought by it, then our final work becomes possible: the creation of ourselves as beings satisfied with that fact.

Sources:

BSWM – Franz Fanon, Black Skin White Mask

ACCP – Aimé Césaire: The Collected Poetry

LSSCP – Léopold Sédar Senghor: The Collected Poetry

RS – Refusal of the Shadow: Surrealism and the Caribbean

MS – Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

NE – Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit and Three Other Plays

ON – Jean-Paul Sartre, Orphée Noir

Francisco de Goya, The Incantation

Francisco de Goya, The Incantation